Alternative Editorial: Let's Not Keep Our Politics Private

In our editorials we’ve often used the term ‘public space’. Although there is more than one explanation for that term, our understanding of what public space refers to is all that the mainstream of society would recognise as the world outside our homes. This would include the rules, rituals and practices we are obliged to accept as citizens, largely because they are necessary due to the prevailing conditions we have accepted as true.

Sounds complicated. But it’s mostly what we take for granted. For example, the received idea that we work eight-to-ten hour days because, unless we did, there would be no services. That we send our children to school (or home school with a similar curriculum) because that’s the only way to get an education. Without which we would be stupid and unable to work.

We take for granted that we vote once every four or five years, because the real work of government is done by politicians who are elected by the people—and that’s because they are the most qualified to do so. Very few of us are political by nature: mostly due to apathy – selfish, distracted, busy! - but also because politics is complicated. And so on.

So when we find ourselves with intractable problems, habitually we believe it is due to the quality of our leaders. After all, isn’t there such a thing as common sense? Any decent and clever person will be able to deliver on that. When we can’t succeed in finding work, or being paid, or becoming part of the tribe of consumers the economy depends upon, we are failing in life. When we have mental health problems it’s because we are weak, probably due to an historically dysfunctional family. When we see protesters in the street, we agree or disagree with their cause—rather than mourn the lack of power they have to live the life they choose.

The globe is a threat to us, so we need to have strong defences. Russia and China might attack us at any time, so we need to be ready to fight if necessary. Nuclear weapons are an effective way of keeping aggressors at bay: no-one attacks a country with enough warheads. The environment is in crisis, but there’s only so much we can do to stop the deterioration: it takes time to change our routines. And how can we be responsible for everyone else’s behaviour?

Eating animals and using their milk for dairy products is natural. The meat industry is not ideal, but slaughtering animals in cruel conditions is unavoidable if you’re going to keep the population supplied with life-sustaining protein. Pets are different from pigs and cows, who have no emotions or relationships.

Of course many of us disagree with this entire picture. But we are living in this reality and the way our society continues to legally organise itself – largely without calling it out. Feel free to add more narratives arising from our public life in the comments below.

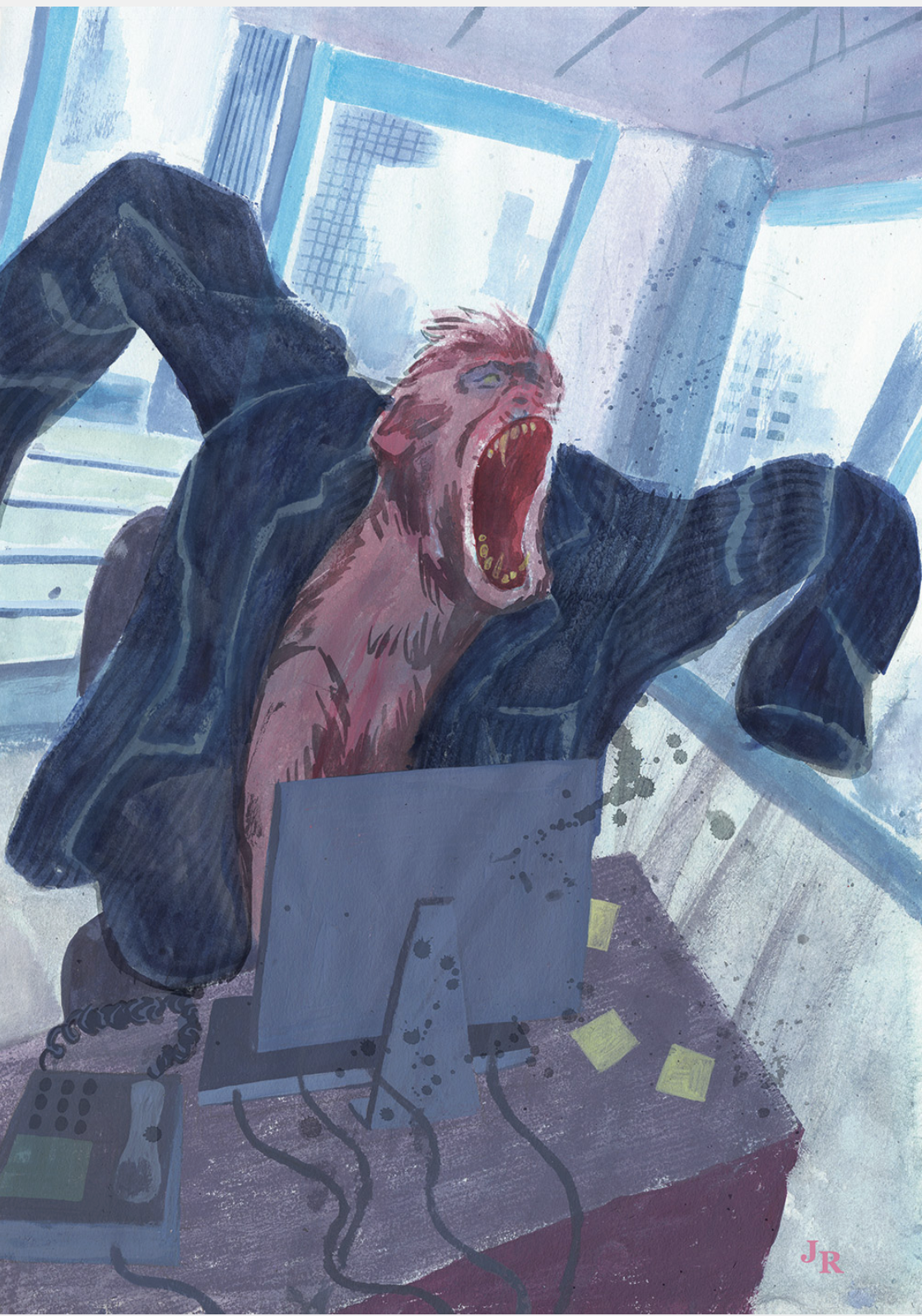

So what happens not in the public but the private space? Given that it’s private it’s difficult to assess accurately, but some of the contrasts to the public space might be recognisable in your world. For example, as much as 85% of us hate working jobs and live for recreation (which rarely happens because we become hedonistic rather than healthy at the weekend) We may not buy the simple deal which authorities of all kinds offer – whether Church, MP or parent – that work, de facto, is the guiding ethic of our society. We might rebel against that, feeling frustrated that our true value as creators is never going to be recognised.

Our children get 60% or more of their education from the internet, because it is more directly relevant to their lives in 2024. School is a game played to keep parents happy but even there, the real authority is the dynamics of the playground (who’s in, who’s out of favour). Being clever is admirable, but being ironic, authentic and original is awesome. When education is finished, the real problems begin. How can young people fit in and thrive in a world they do not rate?

We are afraid of the stories of hostile countries, but we don’t want to fight; who wants to go (or to send their child) to war to die? And what good would it do anyway – those dictators are only out for their own power and don’t care who they kill to get there. Nationalism has become a complicated idea: it’s as problematic as it is empowering. Everything is confusing.

Yearning

Quietly, deeply, sometimes guiltily, many yearn for a different reality. Less stressful, less demanding, more joyful. We find most political issues alienating, but we know what we want and do our best to achieve that for ourselves. What we read in the papers is often baffling: most issues have pros and cons on both sides. We ponder, with little or no space for deliberation even with those closest to us.

Our families and friends have very wide spectrums of ‘views’. Even so we get along because we have fun together and share interests. We generally try to bring our children up to be fair and good and kind and accept that we can’t all be rich – there are other measures of success.

We have constant strong feelings about our lives: we are anxious about the future for ourselves and our children and that’s not personal. That our parents had a different set of challenges than we do today, has nothing to do with whether they were stable or good – our world is in danger because of developments out of our control.

Our lives on the internet are demanding but also amazing: it’s non-stop entertainment and we can buy whatever we like in instalments. Everyone is involved in some kind of self-development – meditation, exercise, making money in new ways. Our sense of who we are is getting much stronger than before: I can find others like me on line. I might not get a job, get married, have children, buy a house – I have choices.

We love animals and nature is amazing – who can argue with that? When people disagree they can talk about it, get over it – especially when they live in the same street or neighbourhood. People can rub along together if they have to.

This is our mapping of the contents of the “private” space in the lives we encounter. But again, please enrich the list your own way, in the comments below.

Why is it important to get real about the difference between the public and private space today – surely it’s always been thus? Maybe: but has it always been as easy as it is now to verify? Largely because, in the world of the internet, this kind of observation and reflection has become commonplace? Online, much of the public and private world has fused. Any form of identity politics for example, begins with a challenge to the norms that frame society. Even our clicked-on “likes” and “dislikes” are serious political fodder now, providing crucial data for politicians. And income for social media providers.

When the distinction between public and private is described as starkly as we have done above, we can see what level of compromise the most of us are accepting. That we are living a lie in many ways, accepting that those with power cannot see the truth of our inner realities. We slide into the belief that we ourselves will never have power: our desires are just that, personal and often unreasonable. That we lack the kind of wisdom that could order our society better. That our best bet is to do our best, get on with life, expecting endless compromise.

Yet some of the behaviours and problematics that our leaders present us with today, might yet be changing the boundary between public and private space. Some are visible and make their way into the mainstream media – for example, the gap between what’s considered fair for politicians and fair for voters (Boris Johnson helped illustrate that on a weekly basis). This causes us to doubt traditional authority.

Yet most of the polarised views of the political classes go unchallenged. For example, “Left v Right” categorises people in ways that deprive each side of some values that all human beings have. The Left are understood to prioritise care while the right prioritise freedom: yet who does not need and want both? Some political fights are unfathomable. Take Pro-Life v Pro-Choice: the very notion is tautological. Both are a choice and both want a life - albeit one emphasises the quality of the mother’s, the other the child’s. Yet women are forced to line up on one side against the others.

In heightened political spaces these differences, arising from a history of debate, cause anger and hatred towards people we have never met. It’s as if politics, amplified by a media with a business model built on divisiveness, enables a dehumanisation of society, or beyond that a full desensitisation. We treat other people as objects to be persuaded, managed, forced; other non-human life forms as distant and undeserving of compassion; the blue planet as a lifeless resource.

We are all familiar with the emotion of ‘hating’ the opposition--whether that means the Tories, or supporters of a football club. Yet in private we quickly back off the idea that we hate anyone. The public space enables the description of people in flight from poverty and oppression as ‘refugees’ without any further acknowledgement of who they are. Some public figures have been allowed to call these anonymous groups ‘vermin’ without being charged with hate crimes. Privately we shrug our shoulders, believing politicians are doing their job.

All of this goes unchecked, because of the chasm between public life and private feeling. In truth, we are all political—in that we have issues we care deeply about and design our lives accordingly. What we may not be is party-political: we don’t align ourselves with one ideology or set of policies until we have to, once every five years. And even then we might only be voting tribally, because we identify broadly with the culture of one over another—quite ignorant of the distinctions being made in Westminster.

Many of us are non-political for the very reason that we cannot abide violent fights between complex positions. And wonder why, at the heart of power, there are not more attempts to agree – as there would be in any family, group of friends or community? The ex-First-Minister Humza Yousaf’s call in the Scottish Parliament this week--for those that are broadly aligned be able to find enough common ground to allow his government to continue—fell on deaf ears.

Clearly, as we painstakingly report each week, there are growing movements of people across the planet who have taken it upon themselves to establish new realities, irrespective of how the mainstream simulates its truths. Whether these are ecocivilisational, spiritual or organisational (co-ops) – or simply anarchic – they tend to aim for autonomy at a personal and social level, disconnecting themselves from government.

Yet given that none of us can disconnect ourselves from the reality of a planet dying, or the lack of resources for those most vulnerable, isn’t it time that more people reclaimed politics on the basis of their inner convictions? To do that, we need a much better architecture for decision making, new attractors that draw people into deliberative spaces and a media system capable of and willing to tell a different story.

Only when these have begun to capture the wider public imagination, can we begin to realise the new political possibilities of Spring: the re-humanisation of the public space, the regeneration of the planet and more integrated, joyful daily lives.