We can't escape disaster stories. But in SF, they can end up as utopias

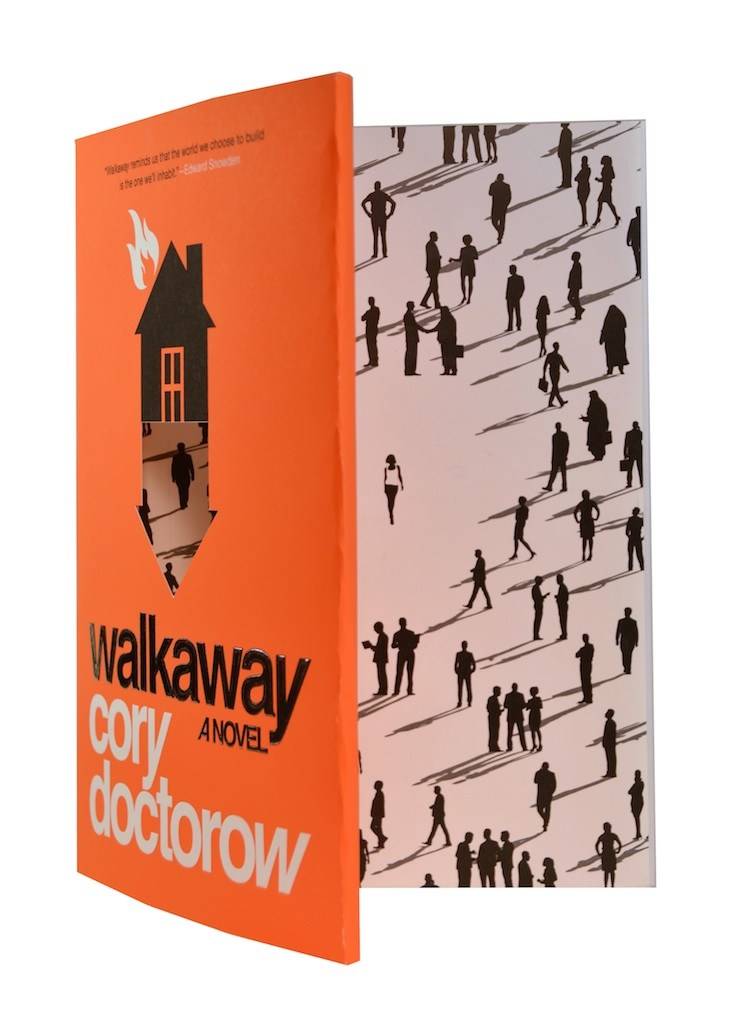

Cory Doctorow is an advocate for internet freedoms, and a brilliant SF writer. He uses the genre to make alternative futures feel human and plausible.

Cory's new book, Walkaway, concerns a near-future society which (says Wikipedia)

...Is a world of non-work, ruined by human-created climate change and pollution, and where people are under surveillance and ruled over by a mega-rich elite, Hubert, Etc, his friend Seth, and Natalie, decide that they have nothing to lose by turning their backs and walking away from the everyday world or "Default reality".

With the advent of 3D printing – and especially the ability to use these to fabricate even better fabricators – and with machines that can search for and reprocess waste or discarded materials, they no longer have need of "Default" for the basic essentials of life, such as food, clothing and shelter.

As more and more people choose to "walkaway", the ruling elite do not take these social changes sitting down. They use the military, police and mercenaries to attack and disrupt the walkaways' new settlements.

One thing that the elite are especially interested in is scientific research that the walkaways are carrying out which could finally put an end to death – and all this leads to revolution and eventual war.

Seems like a dire tale - but Doctorow is at pains to say, in this Wired magazine article, that this scenario of struggle, where the best of human values eventually rises to the top, IS a kind of utopia:

Stories of futures in which disaster strikes and we rise to the occasion are a vaccine against the virus of mistrust. Our disaster recovery is always fastest and smoothest when we work together, when every seat on every lifeboat is taken. Stories in which the breakdown of technology means the breakdown of civilization are a vile libel on humanity itself. It’s not that some people aren’t greedy all the time (or that all of us aren’t greedy some of the time). It’s about whether it’s normal to act on our better natures or whether our worst instincts are so intrinsic to our humanity that you can’t be held responsible for surrendering to them.

Our technology has revealed much of human nobility and cruelty. It’s given us global troll armies, to be sure—but also communities of mutual aid, support across vast distances, mobs of good people effecting one internet-based barnraising after another. Science fiction stories about the net “predicted” both, but the best science fiction does something much more interesting than prediction: It inspires. That science fiction tells us better nations are ours to build and lets us dream vividly of what it might be like to live in those nations.

Last year was full of disasters, and 2017 is shaping up to be more disastrous still—nothing we do will change that. Disasters are part of the universe’s great unwinding, the fundamental perversity of inanimate matter’s remorseless disordering. But whether those disasters are dystopias? That’s for us to decide, and the deciding factor might just be the stories we tell ourselves.