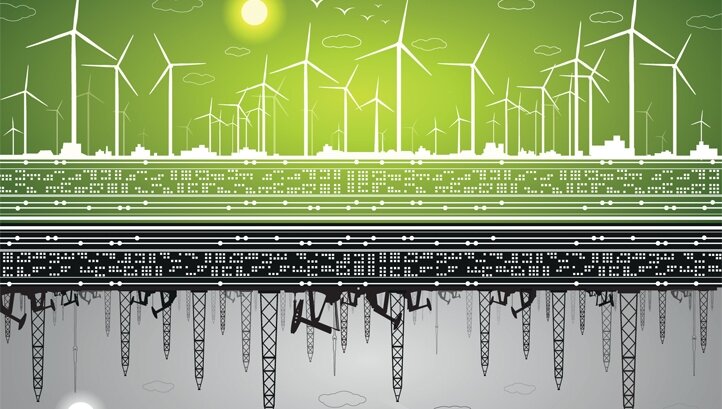

To disrupt the flow of carbon into the atmosphere, we must disrupt the flow of money to coal, oil and gas

Very interesting New Yorker article from the veteran US climate campaigner Bill McKibben, the pioneer of the university disinvestment campaigns. He suggests that the next front to move on to is the way that major banks and funds actively put money into carbon-generation energy. If this could be directed instead towards renewables, would it be a lever we haven’t properly pulled yet to save the planet?

More below:

Climate change is a timed test, one of the first that our civilization has faced, and with each scientific report the window narrows. By contrast, cultural change—what we eat, how we live—often comes generationally.

Political change usually involves slow compromise, and that’s in a working system, not a dysfunctional gridlock such as the one we now have in Washington. And, since we face a planetary crisis, cultural and political change would have to happen in every other major country, too.

But what if there were an additional lever to pull, one that could work both quickly and globally? One possibility relies on the idea that political leaders are not the only powerful actors on the planet—that those who hold most of the money also have enormous power, and that their power could be exercised in a matter of months or even hours, not years or decades.

I suspect that the key to disrupting the flow of carbon into the atmosphere may lie in disrupting the flow of money to coal and oil and gas.

Following the money isn’t a new idea. Seven years ago, 350.org (the climate campaign that I co-founded, a decade ago, and still serve as a senior adviser) helped launch a global movement to persuade the managers of college endowments, pension funds, and other large pots of money to sell their stock in fossil-fuel companies.

It has become the largest such campaign in history: funds worth more than eleven trillion dollars have divested some or all of their fossil-fuel holdings.

And it has been effective: when Peabody Energy, the largest American coal company, filed for bankruptcy, in 2016, it cited divestment as one of the pressures weighing on its business, and, this year, Shell called divestment a “material adverse effect” on its performance. The divestment campaign has brought home the starkest fact of the global-warming era: that the industry has in its reserves five times as much carbon as the scientific consensus thinks we can safely burn.

The pressure has helped cost the industry much of its social license; one religious institution after another has divested from oil and gas, and Pope Francis has summoned industry executives to the Vatican to tell them that they must leave carbon underground.

But this, too, seems to be happening in too-slow motion. The fossil-fuel industry may be going down, but it’s going down fighting. Which makes sense, because it’s the fossil-fuel industry—it really only knows how to do one thing.

So now consider extending the logic of the divestment fight one ring out, from the fossil-fuel companies to the financial system that supports them. Consider a bank like, say, JP Morgan Chase, which is America’s largest bank and the world’s most valuable by market capitalization.

In the three years since the end of the Paris climate talks, Chase has reportedly committed a hundred and ninety-six billion dollars in financing for the fossil-fuel industry, much of it to fund extreme new ventures: ultra-deep-sea drilling, Arctic oil extraction, and so on. In each of those years, ExxonMobil, by contrast, spent less than three billion dollars on exploration, research, and development.

A hundred and ninety-six billion dollars is larger than the market value of BP; it dwarfs that of the coal companies or the frackers. By this measure, Jamie Dimon, the C.E.O. of JPMorgan Chase, is an oil, coal, and gas baron almost without peer.

But here’s the thing: fossil-fuel financing accounts for only about seven per cent of Chase’s lending and underwriting. The bank lends to everyone else, too—to people who build bowling alleys and beach houses and breweries. And, if the world were to switch decisively to solar and wind power, Chase would lend to renewable-energy companies, too.

Indeed, it already does, though on a much smaller scale. (A spokesperson for Chase said that the bank has committed to facilitate two hundred billion dollars in “clean” financing by 2025, but did not specify where the money will go. The bank also pointed out that it has installed 2,570 solar panels at branches in California and New Jersey.)

The same is true of the asset-management and insurance industries: without them, the fossil-fuel companies would almost literally run out of gas, but BlackRock and Chubb could survive without their business.

It’s possible to imagine these industries, given that the world is now in existential danger, quickly jettisoning their fossil-fuel business. It’s not easy to imagine—capitalism is not noted for surrendering sources of revenue. But, then, the Arctic ice sheet is not noted for melting.

The last minutes of a football game are different from the rest; if you are far enough behind, you dispense with caution. Since gaining a few yards cannot help you, you resort to more desperate, lower-percentage plays. You heave the ball and you hope, and, every once in a while, you win.

So a small group of activists has begun probing the financial industry, looking for chances to toss the kind of Hail Mary pass that could yet win this game. The odds are definitely long, but just talking with these groups has begun to lift my despair.

….This all could, in fact, become one of the final great campaigns of the climate movement—a way to focus the concerted power of any person, city, and institution with a bank account, a retirement fund, or an insurance policy on the handful of institutions that could actually change the game.

We are indeed in a climate moment—people’s fear is turning into anger, and that anger could turn fast and hard on the financiers. If it did, it wouldn’t end the climate crisis: we still have to pass the laws that would actually cut the emissions, and build out the wind farms and solar panels. Financial institutions can help with that work, but their main usefulness lies in helping to break the power of the fossil-fuel companies.

Most of the N.G.O.s already at work taking on the banks and insurers, which include many indigenous-led and grassroots groups, are small; often they’ve had no choice but to focus their efforts on trying to block particular projects.

(The vast Adani coal mine planned for eastern Australia has been a particular test, and at this point most of the world’s major banks and insurers have publicly announced that they’ll steer clear of involvement.) Imagine, instead, this financial fight becoming a fulcrum of the environmental-justice battle.

Even if that happened, victory is far from guaranteed. Persuading giant financial firms to give up even small parts of their business would be close to unprecedented. And inertia is a powerful force—there are whole teams of people in each of these firms who have spent years learning the fossil-fuel industry inside and out, so that they can lend, trade, and underwrite efficiently and profitably.

Those people would have to learn about solar power, or electric cars. That would be hard, in the same way that it’s hard for coal miners to retrain to become solar-panel installers.

But we’re all going to have to change—that’s the point. Farmers around the world are leaving their land because the sea is rising; droughts are already creating refugees by the millions. On the spectrum of shifts that the climate crisis will require, bankers and investors and insurers have it easy.

A manageably small part of their business needs to disappear, to be replaced by what comes next. No one should actually be a master of the universe. But, for the moment, the financial giants are the masters of our planet. Perhaps we can make them put that power to use. Fast.

More here. We have begin to explore the relationship between finance and climate crisis here.