Battery Lives: Tesla's super-batteries beat fossil fuels. But is the lithium they need becoming as geopolitically toxic as oil?

The Uyuni salt flat in Bolivia (from New Republic)

There are some techno-fixes to climate change - but we have to constantly review them, to ensure they don’t just replicate the old structures of exploitation and neo-colonialism that oil, gas and coal established.

A case in point is battery storage technology. It’s essential if the fluctating supply of renewable energies is to be stabilised, and able to provide a “baseload” (a constant supply of electricity) that is competitive with other, more toxic energy generators (like nuclear, or fossil-fuel powered stations).

If you’re already a co-creator, click here. And if you can, please contribute!

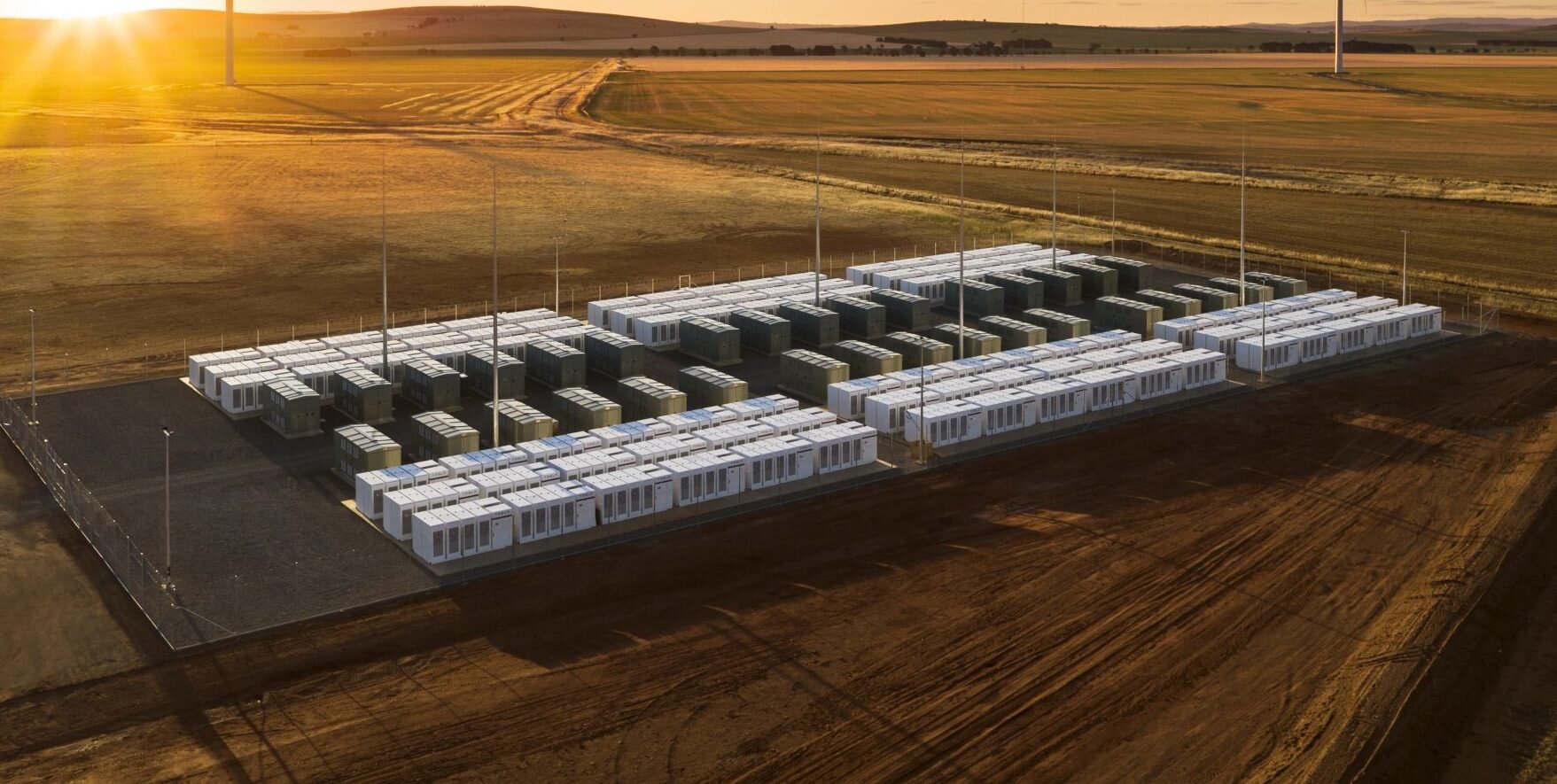

Tesla’s massive Hornsdale battery in South Australia is proving to be a superstar example of how giant batteries are shaping our energy futures.

This story from Teslarati frames it in competition with fossil fuel generators, as they respond instantly to fluctuations on the wider Australian energy grid. Filled with wind and solar power, the Tesla batteries respond twice as quickly to such emergencies. The story casts these benefits as “savings” to consumers who are now barely inconvenienced by energy-grid fluctuations.

TESLA BIG BATTERIES AT HORNSDALE POWER RESERVE SOUTH AUSTRALIA (from Teslarati)

Yet these are massive lithium-ion batteries - and the lithium must come from somewhere. As the New Republic’s Kate Aronoff reports, viewed from the perspective of Bolivia - one of the centres of lithium minng in the world - it looks like becoming the same kind of “resource curse”, in terms of political insecurty, as fossil fuels once were for developing countries. The deposition of President Morales was murky - Morales had hiked up the prices and nationalised lithium production in recent years.

As Aronoff continues:

With the country in disarray, the future of lithium in Bolivia remains uncertain. South American lithium extraction for now is concentrated in Chile and Argentina. Workers and indigenous communities have protested destructive mining practices in those places too, but with far less sympathetic national governments, who are more eager to please multinational corporations.

Meanwhile, demand for lithium is set to explode. Building a green energy grid, expanding renewables and electrifying everything from cars to cooktops requires more lithium and other so-called technology metals that are central to clean energy. The Institute for Sustainable Futures, for instance, projects that a world run fully on renewables by 2050 would demand 280 percent of the planet’s lithium reserves—those which are economically viable to extract—and 85 percent of the planet’s total lithium resources.

It seems like an impossible bind: Even if the global economy manages to transition off of fossil fuels it will simply sub out one kind of harmful extraction for another. The future of technology metal mining in South America and elsewhere could look eerily similar to centuries of colonial exploitation, dressed up as environmentalism

American highways could buzz with Teslas traveling between sprawling suburban rooftops and office parks decked out in solar panels, all premised on capitalist profiteering and disregard for indigenous rights. Moreover, given Chinese firms’ domination of the lithium industry, we could see geopolitical conflicts akin to previous ones over oil.

What’s the way out of this? Aronoff looks - a little mistily, it must be said - at the improving prospects of an American Green New Deal, outlining

…the role the United States could play in reimagining a global order that for centuries has relied on an exploitative transfer of wealth from the resource-rich but less-developed South to the wealthy North.

It’s hard to predict the full scope of what the U.S. could do if it earnestly worked to remake the global economy along more egalitarian lines—for example, seeking collaboration with China and other countries rather than destructive trade wars—in order to meet the climate challenge head-on.

Instead of meeting new demand for technology metals wholly through new extraction, U.S. policy could work to harvest them from the electronic waste or the byproducts of other types of mining, where these substances are abundant.

The sheer purchasing power of a U.S. government committed to making its transportation system run on renewables could set a global standard for labor, indigenous and environmental rights in minerals extraction, ensuring the benefits of a green transition flow up and down the supply chain. It could rewrite trade agreements in ways that prioritize democratic governance over multinational corporations.

More here. However, we won’t be holding our breath, either in the US or the UK.

And in the meantime, there might be less centralised, more distributed ways that our existing battery power - say, the vehicles in our driveway - could be used to support baseload supply (see for example this Daily Alternative post from last year).