Doughnut economics: gamified by Seeds GameLab, and illuminating the future viability of Mexico City

We love to chart the advance of Doughnut Economics throughout the world - doing its job of framing the balance between environmental limits and urban possibilities, in an easily graspable and actionable way. Here’s two new great examples.

Seeds GameLab: Gamifying the Doughnut

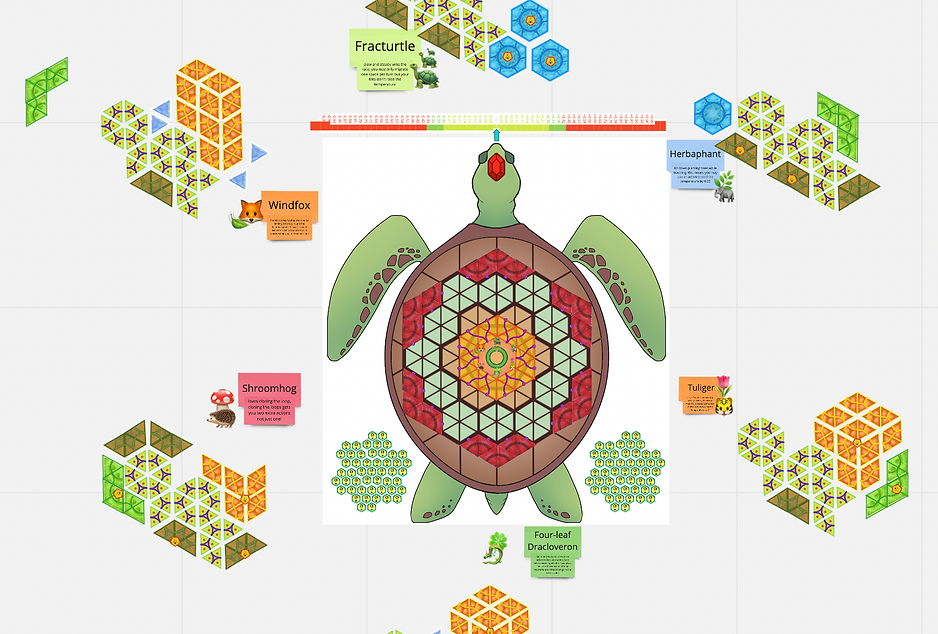

Seeds GameLab has been trying to experiment with making games that bring people into an understanding of doughnut economics for the last year or so. Some examples are

Games offer a safe space for people to step outside their rational minds and intuitively explore new narratives and behaviours. Based on this insight, we brought together a group of twelve volunteers to co-create the story of doughnut economics in game form. We draw from expertise in biomimicry, ecological design, linguistics, digital art and systems thinking to create an experience bigger than the sum of its parts.

The game aims to:

Provide an intuitive understanding of doughnut economics principles.

Reward collaborative, reciprocal, and regenerative actions.

Change the way people conceptualize the purpose of the economy, the relationship between society and the environment and the idea of success.

Empower people to take action within their communities to live regeneratively.

Some slides of the game:

Other games include Serendicity, an app-based game which aims to close - in a fun way - the intention-action gap.

Their basic theoretical background assumptions are interesting and coherent:

Findings in the field of Behavioural Economics have demonstrated a host of ways in which our environment (both cultural and spatial) shapes our behavior and incentives through unconscious priming effects.

A prime is an unconsciously perceived environmental stimulus that can influence a person's subsequent thoughts, feelings, and responses. One experiment conducted by Kathleen Vohs in 2006, the presence of an irrelevant money-related object such as a stack of Monopoly bills caused participants to display more individualistic attitudes like self-distancing.

Similarly, insights from Sarah Goldhagen (2017) show that the organizational and built environments we occupy are filled with primes, and because that is so, a well thought out organizational design can be deliberately composed to nudge people towards regenerative and fair choices.

This begs the question of which behaviors have our cultural, organizational and built environments been priming over the past few centuries and how can these be changed to pave the way towards regenerative and fair economies?

This project harnesses the awareness-raising and immersive qualities of gaming to bridge the gap between circular economy theory (focusing on Kate Raworth’s Doughnut economics). When playing together, people are not just having fun but are actively re-patterning their thoughts and behaviours to imagine a world that doesn't exist yet but someday might.

Mexico City is a great big potential doughnut

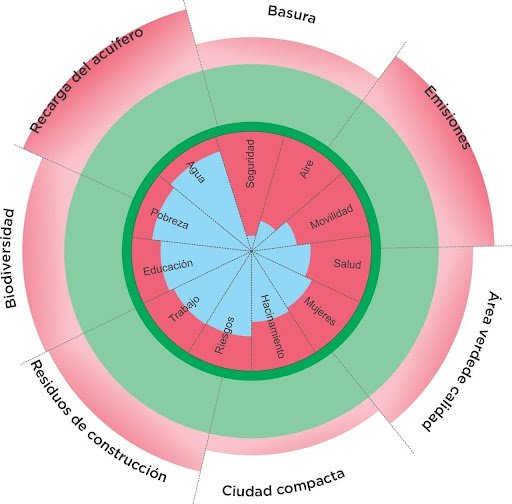

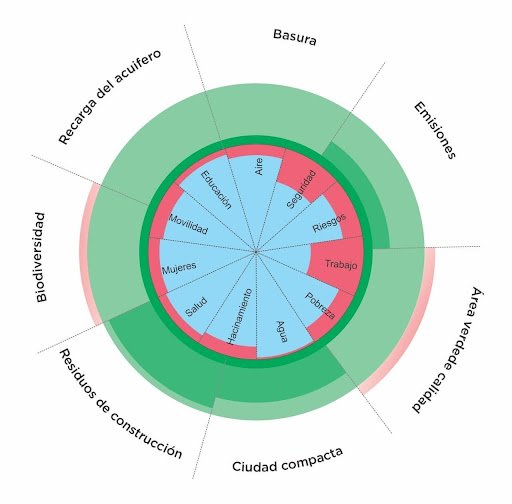

On the left, Mexico City’s doughnut profile in 2020. On the right, a plausible model for 2040

This piece from Apolitical is written by a team at Coordinacion de Asesores y Asuntos Internacionales del Gobierno de la Ciudad de Mexico. Above is what they imagine could be possible for Mexico City’s sustainable development over the next twenty years. They explain the diagrams below:

Kate Raworth’s "doughnut economics" provides a powerful tool to communicate development challenges. The circle in green represents a situation where all basic needs are met and there is sustainable use of natural resources. The green “doughnut” is the ideal society where people want to live. Figure 1 presents a "doughnut" for the current situation in Mexico City. It incorporates 11 social dimensions and seven environmental challenges.

The gaps (in red) in the inner circle represent the effort that needs to be done to go from the current level in each particular dimension of welfare to the level where we want to be in the future. Taking the example of education, the proportion of youth that has completed 15 years of formal education (middle-high school) in the city in 2020 was 27%. If we want to increase that proportion to 80% in 20 years, we know we have a big gap to fill.

Furthermore, taking that proportion to 99% of young people would require additional efforts beyond the 20 years plan. Following the same logic for each dimension, we have a good representation of the challenges to be met in all priority dimensions of welfare; all the red flags in education, health, poverty, housing, water provision, the conditions of labour, public transportation, air quality, and security.

A similar logic applies to the red areas outside the doughnut: they represent infringements on environmental sustainability. In Mexico City, overexploitation of water resources, for example, is compromising water availability in the future. Restoring sustainability to water resources will need great efforts, reducing overexploitation of the aquifers and a more efficient water distribution system - until we touch the outer perimeter of the doughnut and the water balance is restored.

Similarly, public policies would have to address the key dimension of the environment to restore sustainability: GHG emissions, the loss of biodiversity, and waste disposal, to name a few.

A long-term plan with a clear vision of the direction in which we want to take the development of the city can be represented in the “doughnut” 20 years from now (Figure 2). The implementation of ambitious yet realistic policies in all priority areas would result in a much better place to live in.

Some gaps, mainly in the social dimensions of development, will require the continuation of effective policies to reach the aspirational level of development. Comparison between the current and future “doughnuts” provides a clear and powerful image of the efforts needed to achieve socially desirable goals for improved welfare and environmental sustainability.

These graphical representations help to stimulate a discussion about the policy options and the cost of closing current development gaps.

Clearly, 20 years are not enough, but smaller gaps (red areas) in both the social and environmental dimensions of development are pointing in the right direction. Ending corruption and an efficient management of public resources, consistent with a shared long-term vision of development, will take us much closer to the green area of the circle—the space where we all want to live in.

The purpose of this exercise is to present a suggestive picture of our development challenges and to facilitate the public debate on policy options and the cost of alternative routes to development that will help us identify the issues to tackle by public policies now and in the future.

More here. And for updates on DE, go to their activity feed.