The car-based street trashes society (but lets you park at your door). The human-centred street lets much more flourish

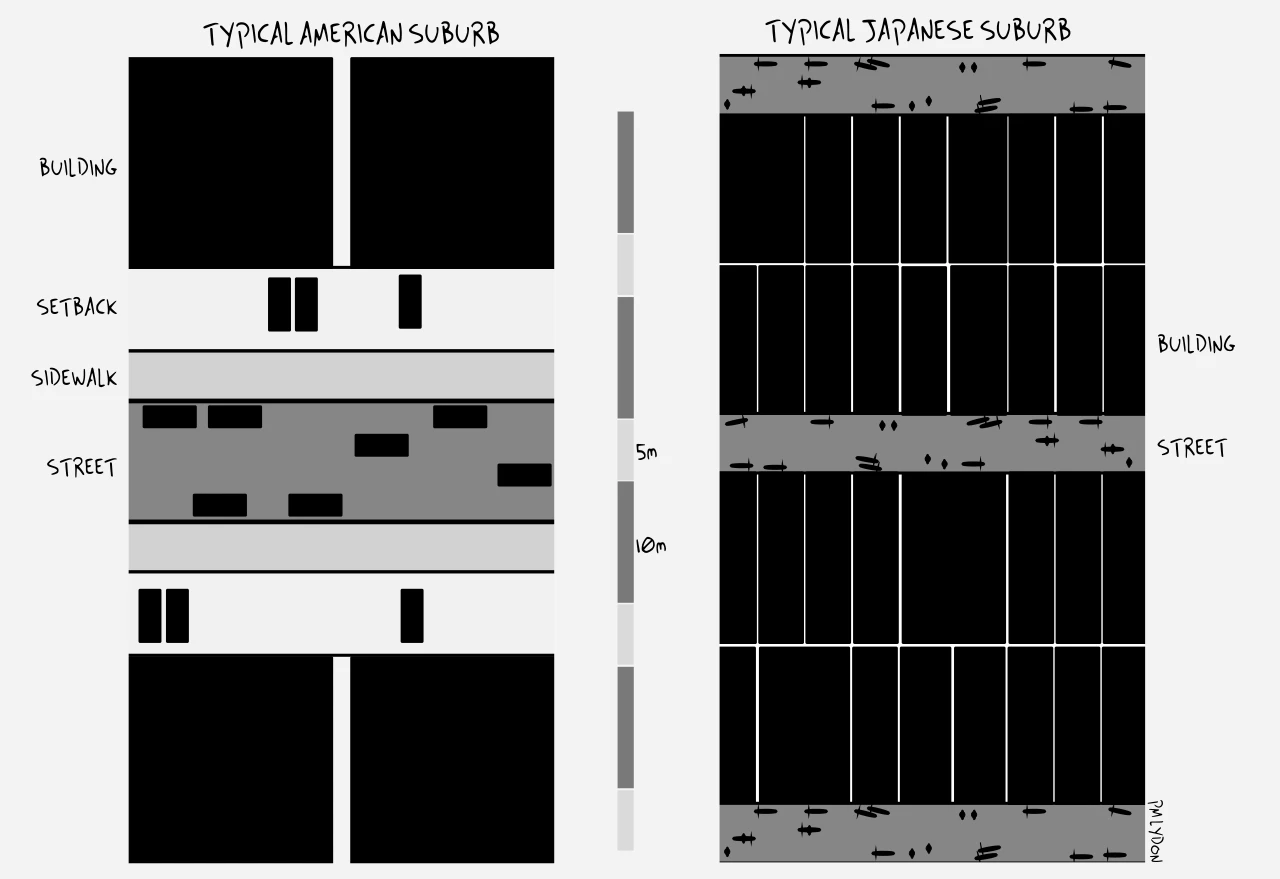

A great example of concrete green lifestyle: how should a human-centred, as opposed to a car-centred street, actually work? What design decisions do you make? This blog from Patrick M. Lydon’s The Possible City shows how. Look at the illustration above, then read the text below:

Ben pulled up on his bike and knocked on the door this morning. We opened the window and said hello. His 6-year-old daughter was excited to show us that she lost her two front teeth. She smiled from her seat on the back of Ben’s bike. They were on the way to the market and, with Suhee and myself at the window, we arranged dinner plans with Ben for next Friday at his house.

“It’s hamburger day,” Ben declared. Then, the smiling new-teeth-sprouting daughter and the bearded bicycling dad pedaled off to the store. Likewise, we will pedal over to their house on Friday.

It wasn’t until after Ben rode off that I thought how convenient, enjoyable, and unique that little exchange at our front window was. It can only happen as it did, in a neighborhood where where streets and alleys are small (narrow) enough, so that a house can directly snuggle up to the edge of the street in a comfortable way.

Can you spot Ben and his daughter [illustration above]?

Patrick goes on to illustrate two street design scenarios - the car-based and the human-based:

To understand what makes a street ‘comfortable’ enough, that one would accept having their front door and kitchen window open directly onto that street, let us imagine two, somewhat opposite, scenarios:

Scenario 1: A typical ‘car-based’ wide street neighborhood

Suburban American and European streets often include space for sidewalks, for street parking, and for two-way car traffic. It is a utilitarian arrangement, but offers few opportunities for interactions like the one described above.

Design:

For safety and relative peace, homes in this scenario are normally ‘set back’ from the street. The empty space created by this set back is then used for a front yard or car parking, or some other kind of buffer zone.

The wideness of the street, plus the sidewalk, plus the setback creates some unintended consequences however, one of which is that cars tend to travel at higher speeds than they probably should.

To combat this, cities implement a slew of mechanisms—speed bumps, signs, cameras, traffic police, bollards, painted crosswalks, flags, flashing lights—in an attempt to make the street safe. These mechanisms often fail.

Social result:

Occupants and users of buildings are distanced from everything that happens in the street, giving less opportunity for interaction between people. Vehicle traffic moves more quickly and carelessly, creating dangerous situations for pedestrians. Most of the space apportioned to cars and people goes largely unused at most times of day.

This makes for pretty boring, underutilized spaces that tend to be ecologically unfriendly, prone to crime, and require a heavy taxpayer burden to build and maintain. But in exchange for all of that, we do get to drive our cars to our doorstep.

On the left, a typical American suburb, on the right, a typical Japanese suburb, both built around the 1970s. Note how both the street and entire bock of Japanese homes fits within the American street-sidewalk-driveway space.

Scenario 2: A typical ‘human-powered’ narrow street neighborhood

Streets here are just wide enough to facilitate walking and cycling, as well as to ensure sunlight to the buildings. In some cases there is room for a single, small motor vehicle to navigate carefully, but not to park.

This environment encourages slow movement by ‘human-powered’ means—walking, wheeling, cycling and the like, increasing opportunity for human interaction.

Design:

The street atmosphere is generally comfortable and safe for humans to inhabit directly, so homes are placed on or near the property line fronting the street. Though there is no space for a front yard, there are front ‘gardens’ that exist as planter boxes set up against a home, with plants growing vertically.

This leads to naturally occurring (as in: not-master-planned) human-scale, garden-like atmospheres within many of these streets. There is no practical need for a sidewalk or setback on such an alley, and certainly no need for a crosswalk, flashing lights, or any of the other safety mechanisms required in the car-based neighborhood.

This is an efficient use of space that provides many economic and livability benefits for occupants.

Social result:

Home (or shop) occupants here are close to the action on the street, leading to a high level of interaction between neighbors. The varying ‘narrowness’ of the street courtesy of individual box gardens, small trees, bicycles, and conversing neighbors, also creates a space where through traffic is forced to move slowly on foot and bicycle.

There is very little wasted space in such alleys and the streets are well visited. Jane Jacobs might be quite happy here. If varied uses occur at different times of day—our particular alley in Osaka includes independent shops, a neighborhood pub, and small offices in and amongst the homes—these alleys are alive, safe, and incur a much lower cost to the taxpayer base.

However, while bicycles can be parked in front of homes, cars must find another place to park nearby.

***

There are various versions of what a street can be, in-between the two extremes of the American suburb and the Japanese alley. I prefer the alley, where I can make dinner plans through the kitchen window!

What kind of street do you prefer?