Alternative Editorial: Pat Kane on the need to be militant about our imaginations, too

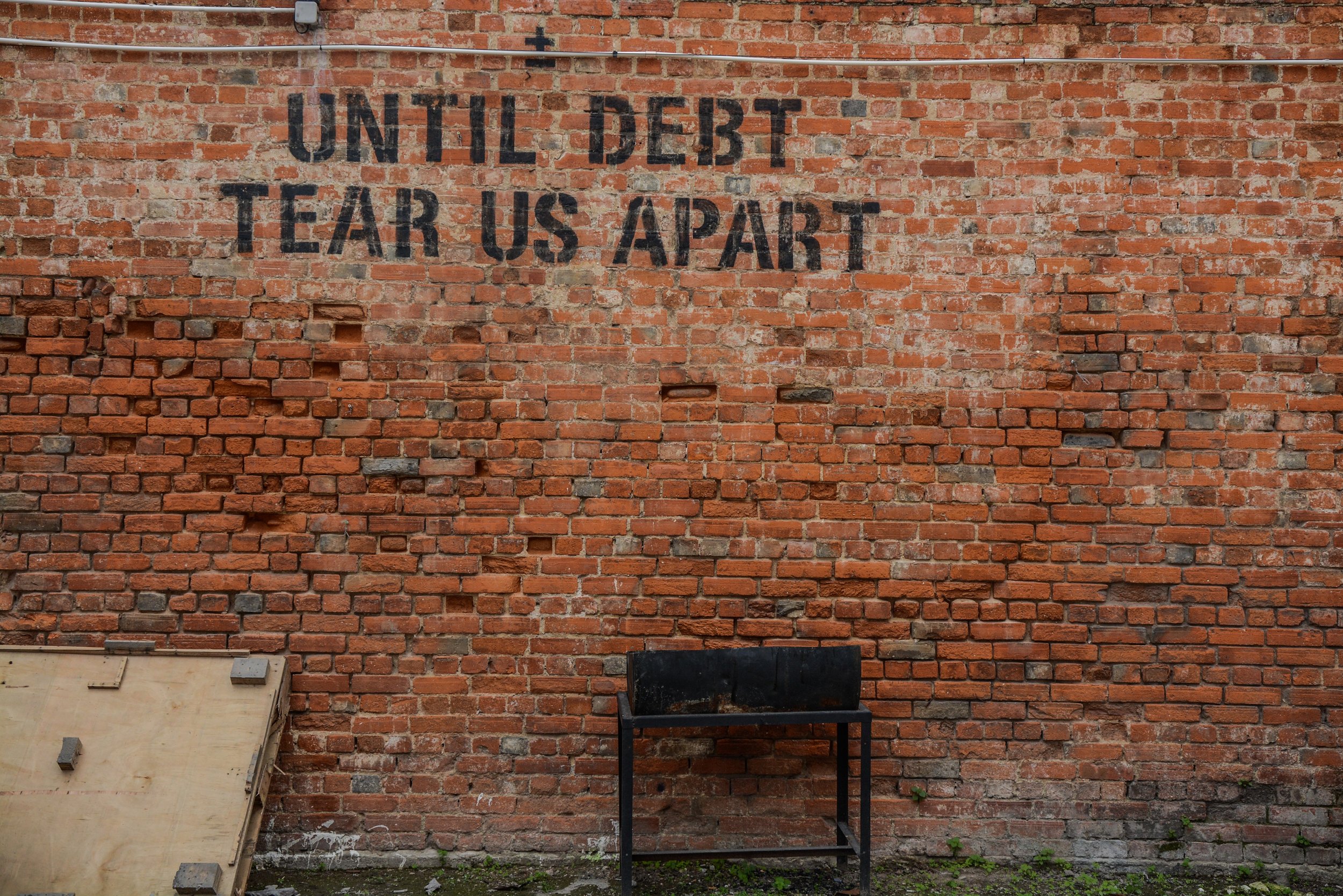

Photo by Alice Pasqual on Unsplash

We are taking a summer’s rest in August from daily blog posting - but we are running some weekly editorials from Alternative Global co-initiators, and friends of the site, over this month. Here’s the first, from Pat Kane, co-initiator of the Alternative Global with Indra Adnan. Pat wonders if our imaginations also need to be enlisted in the current surge of UK protests.

* * *

PK: It’s going to be a very demanding winter on these islands. Energy price rises are advancing at a terrifying rate - predicted to be up 70% between October and December 2022 (and that’s on top of previous bruising increases). This is more like lurid science-fiction than standard market fluctuations.

How will citizens cope? Partly, it would appear, by reviving some familiar forms of civic and social militancy. Charismatic trade union leaders - like Mick Lynch of the RMT transport union - are landing their case, for once. Corporate elites are making fortunes from these under-regulated price rises, while workers’ wages have lagged well behind inflation for many years.

Pointing this out clearly - and especially in the zombie-like context of a Tory leadership contest - appears as a revelation to many.

And reminiscent of the non-paying poll tax protests of the late80s/early 90s, Don’t Pay is trying to amass a million people, pledging not to pay their astronomical energy bills on October 1st of this year. 17 million refused to pay their poll tax, which led to its removal in 1991. The non-aligned (as far as we can see) Don’t Pay aim to get to that critical mass.

As moves to defend and protect the vulnerable, under egregious conditions of inequality, this kind of traditional militancy is perfectly understandable - and justifiable. To some extent, anything beyond a suffering, exhausted quiescence is a response you’d prefer.

But from an Alternative perspective, we should also keep an eye on the wider context of these struggles - primarily the climate crisis. The economist James Meadway has recently been suggesting that the “cost-of-living” crisis points to a harder, deeper truth than talk of “runaway inflation” and “wage-prices spiral”.

What if climate upheaval, and the disruptions to supplies of commodities it causes, is simply making our products and services more costly? As Meadway put it recently (and succinctly), “there is no wage low enough [or interest rate high enough] that will end the floods in Brazil that have damaged coffee production. Or call off the plague of locusts in East Africa. Or remedy droughts in Taiwan, which put the hugely water-intensive production of semiconductors at risk”.

Or, for that matter, will it represent an adequate response to Putin’s territorial adventuring—enabled to some degree by Europe’s energy dependence on Russia’s high-carbon supplies.

Relying on authoritarian regimes across the globe for your energy sources is a wake-up call. But it’s still not quite as loud as the call for a vertiginous drop in material consumption in the Northern hemisphere, in order that we don’t accelerate the effects of global warming.

Meadway lays out clearly the kind of collective policies that would “restructure the economy around resource-minimising consumption. That means reduced working time, more public holidays, more social spaces, more provision of care and education, more digital consumption. All still resource costs” notes Meadway, “but all of them more efficient than high material-use alternatives”.

In essence, Meadway’s response to the “cost-of-living” question is to expand and value those structures and practices that make “living” cost “less” to individuals, families and communities. His list above supports convivial, participative and relational activities – people-to-people, not purchase of stuff. (Though Meadway also demands that excess corporate profits be taxed).

The environmental campaigner George Monbiot, riffing on JK Galbraith’s ‘private affluence, public squalor”, calls this “private sufficiency, public luxury” in his Schumacher lecture:

Everybody wants a good life, we all want to share in the natural wealth of the planet, we want to share in prosperity, we want to live decently, we don’t want to be excluded, we don’t want to be marginalised, we don’t want to be so poor that we have a rubbish quality of life. But how can we possibly attain all that if there isn’t enough space?

Well, there is. There’s not enough space for a private luxury, but there is enough space for everyone to enjoy public luxury. If only we use the space more intelligently, there is enough space for everyone to enjoy magnificent public parks and public swimming pools and public museums and public tennis courts and public art galleries and public transport.

By creating public space we create more space for everybody, whereas when we create private space, we exclude the majority of people and create less space for others.

Regular readers of the Alternative will find Meadway and Monbiot’s prescriptions familiar. But they will also be familiar with our objection - that acting upon the “public” and the “social” in this way usually requires a national state that’s been captured by progressive forces, through the processes of representative democracy. Is that pre-condition plausible?

Look at the Tweedledum of UK Labour’s accommodating response to the hard-Brexit Tweedledee of the Tory leadership race. Does this encourage you to imagine that parliamentary success is a route to shaping this shift to a low-material lifestyle, at an institutional and legislative level?

We try not to wait for that ratchet to rustily click into place in the Alternative. But it’s then incumbent on us to suggest parallel pathways and practises.

We might cite veganism as an exemplar. Here’s how a profound shift in personal and social practice - eg, your food choices - can provide pleasure/attraction (those armies of cheeky vegan cooks on Instagram).

But veganism can also easily tie your everyday decisions to planetary implications (as eliminating meat from your diet makes a huge dent in greenhouse gases like methane). There’s also no shortage of community and culture that can support you in your choices.

How could veganism’s process be extended to other low-material practices - like energy-efficient housing, locally-generated renewable energy, sense-making tools for communities?

This is the point of our work in both theorising, and building, CANs (citizen action or community agency networks - see our category). It feels just as important to be militant about community imagination—to assert visions, desires and possibilities, with a worldly and cosmolocaltone—as it is to be militant in more traditional ways.

If Meadway’s analysis is right, and we are facing not just a cost-of-living but a cost-of-everything crisis, then we have be both bold, and concrete, about the futures we want in these circumstances.

There have been many recent projects, funded philanthropically or civically, which have dwelt on subtle methods of coordination, co-creation and collective imagining.

Maybe the next stage of these strategies could apply themselves to the local infrastructures, technologies and systems immediately and urgently required. Can becoming resilient in energy, food, housing, transport, media and more, feel like a fantastic thing to do?

Can the intensity of longing, and the detail of imagining, a post-consumerist future be raised like a civic wave—with culture and activism well upstream of politicians, who would ideally scamper after the people?

Look at our Daily Alternative categories of “localism”, or “Yes We Can”. There you’ll see many scores of projects that are actively prefiguring such futures.

At the Alternative, we are always particularly sensitive to the emotions and motivations, the personal dimension, behind effective activism. The Human Givens framework, with its nine emotional needs, is regularly used in our analyses and initiatives. But an interesting take comes from Pankseppian affective neuroscience (AN), which has a different seven-strong take on our evolutionarily functional emotional drives.

In AN's dashboard, there is a place for tapping anger and fear – expressed as the righteous indignation of protest - about the immiserating policies of our current elites. But we can also go to the emotional primes of care, play and curiosity. Our evolved needs to protect the vulnerable, to joyfully test out our options, to tap into our desires and yearnings…

All of these can be the fuel for imaginative social and civic initiatives, which we highlight each week here, hoping that our CAN framing can intensify them. (Note that the science of emotions is a highly contested field at the moment).

In short, we “unbreak” politics when we build positive and innovative new things: projects that make people feel like surging, creative agents in their lives, not just “the workers” or “those to be mobilized”.

Perhaps, seen from all these angles, this tough winter might end up becoming a kind of spring, after all.