"Infrastructure is always an act of solidarity with people who aren’t born yet." Cory Doctorow on tech's role in the climate crisis

From NYT

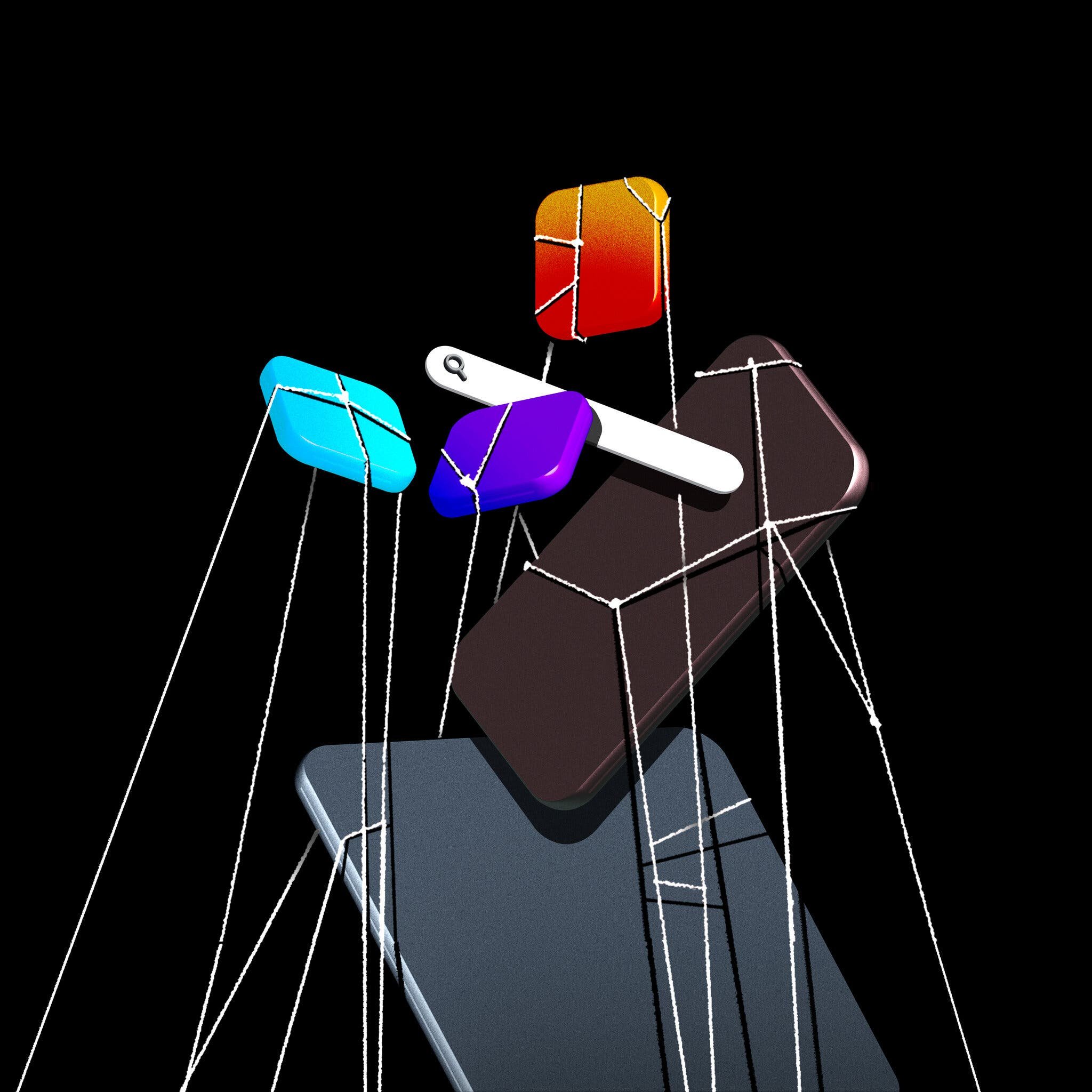

Cory Doctorow’s viewpoint on technology is very close to our own. “Technology isn’t the problem”, he writes in The Internet Con. “We should stop thinking about what technology does and start thinking about who technology does it to and who it does it for.”

This recent interview with Jacobin is expansive, but we’ve selected the climate-change question and answer at the end.

Jacobin: To what sense does technology play a critical role in addressing climate change? And to what extent is it used as a tool to undermine climate action? The concentration of technological power can significantly hinder climate action, making it challenging to enact effective mitigation measures. To what extent can liberating technology from this concentration improve mitigation efforts?

Cory Doctorow: Let’s start with just how those mitigation efforts are going to require the deployment of technology. Deb Chachra is a leftist material scientist. She has a book coming out in mid-November called How Infrastructure Works.

And it’s a very good book about what infrastructure means, because infrastructure never amortizes over the life of the people who build it. That’s kind of one of the defining characteristics of infrastructure.

Infrastructure is always an act of solidarity with people who aren’t born yet, and infrastructure always requires planning that goes beyond what markets can accomplish.

The book makes quite a profound insight. And as she digs into the nitty-gritty of infrastructure, one of the points that she makes is that you could give every human being on earth the energy budget of a Canadian, which is like an American energy budget, but colder.

We could give every person on earth a Canadian energy budget by capturing 0.4 percent of the solar radiation that passes through our atmosphere. We have access to effectively unlimited energy, but we have severely limited materials with which to capture that energy.

And we all are familiar with what happens when we don’t manage our material cycles well. You get microplastics in the water and in our bloodstream, you get carbon in the atmosphere, you get poison and privation and despoilment.

For most of human history, we’ve operated under the assumption that materials were abundant, and could be used once and then discarded, while considering energy to be scarce. And the reality is that we receive a constant influx of energy every time the sun or the moon rises, and new materials only arrive on Earth when a comet manages to survive entering our atmosphere.

A rational, technologically informed program of sustainable circular material use that trades energy for material is important. For example, it might be energy intensive to recover the lithium from a battery at the end of its duty cycle. But this energy intensity becomes less critical if we use the lithium to manufacture batteries and other conflict minerals to create solar panels.

This could allow us to capture solar energy and use as much of it as needed to replenish these materials when they reach the end of their life cycles. There’s a point at which, through wise stewardship — if we can attain liftoff — we can inhabit a world of great abundance that does not come into conflict with the habitats and biota that we share it with. And ultimately, we need something beyond what markets can deliver to get there.

People seizing the means of computation is key to having that better future, that sustainable future, that future that allows us to live well and responsibly. To navigate this path, speaking to someone who dedicated their teenage years to activism, cycling through the streets of Toronto armed with a bucket of wheat paste and a ream of handbills to plaster to telephone poles, I can confidently tell you that organizing global mass movements will not be possible without harnessing the power of technology.

And so the people in the book inhabit a future where they’ve adeptly leveraged technology to navigate their way out of the current crisis. They employ technology not only to address the immediate challenges we face. They also engage in the long-term battles required for constructing the extensive infrastructure essential for multigenerational work.