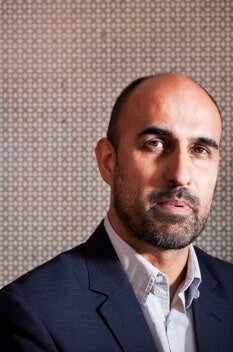

Writing truthfully in these whirlwind times, says Hari Kunzru, requires courage, wit, skill, judgement and cunning

From New Yorker

In an environment where “fake news”, declaimed from on high, sends any possibility of an agreed social truth into a tailspin, we applaud the courage of the writer Hari Kunzru in this essay from CanopyCanopyCanopy. Hari hazards a few defintions of what counts as truth for any writer in this current circumstance - but he takes his headlines from this classic paragraph of Bertolt Brecht:

These days, if you want to struggle against lies and ignorance, and to write the truth, you must overcome at least five difficulties.

You must have the courage to write the truth when everywhere truth is repressed.

You must have the wit to recognize the truth, though everywhere it is concealed.

You must have the skill to make the truth into a weapon.

You must have the judgment to choose those in whose hands the truth will be effective.

And you must have the cunning to spread the truth among such people.

We recommend Hari’s full 3516-word essay, but here are some choice extracts:

The Courage to Tell the Truth

It seems obvious that, as a writer, you should write the truth, in the sense that you ought not to suppress or conceal anything or deliberately write things that are untrue. You ought not to bow down before the powerful or betray the weak.

It is, of course, very hard not to bow down before the powerful, and it is highly advantageous to betray the weak. To displease the possessors means to become one of the dispossessed.

To pass up paid work or to decline fame when it is offered may mean being unpaid or unknown forever. This takes courage.

…It takes little courage to mutter a complaint about the triumph of barbarism in a place where complaining is still permitted, even prized. Many writers pretend that the guns are aimed at them when, in reality, they are merely the targets of influencers, trackers, and ads.

They shout their generalized demands to a world of friends and followers. They insist on a generalized justice for which they have never done anything. They ask for generalized freedom: Alexa, make the government change.

These writers think that truth is only what sounds good. If the truth turns out to be difficult or dry, they don’t recognize it as such. Because what they crave isn’t the truth but a feeling and a status: the feeling of truth, the status of being a truth-teller. The trouble with them is: they do not know the truth.

The Wit to Recognize the Truth

…It is not untrue that a rose is red and that rain falls from the sky. Many poets write truths of this sort. Our first difficulty – the question of courage – does not trouble them. Their consciences are clear. The powerful can’t corrupt them, but they are not disturbed by the cries of the oppressed. They go on writing.

At the same time, it is not always easy to realize that their truths are truths about roses or rain; they usually sound like truths about important things. They might say that the President is corrupt, or the government has been captured by oligarchs. But when you look closer, you see that all they’re saying is that a rose is a rose, and no one can stop the rain from falling. They do not discover the truths that are worth writing about.

On the other hand, there are some writers who deal only with the most urgent matters, who embrace poverty and do not fear the rulers, and who nevertheless can’t find the truth. Why? Because they lack knowledge.

In this age of distraction and lightning change, what is needed is knowledge of the material basis of things. This is the kind of truth that allows people to take action.

As a writer, you can write that you find it beautiful to be loved. You can write that it is sad to lose your lover. But if all you do is record your little epiphanies, you won’t be able to arrange the things of the world so that they can be controlled. Yet the truth that I am talking about has this function and no other.

The Skill to Manipulate the Truth as a Weapon

You must speak the truth with a view to the results it will produce. That is to say: action…

…We live in an algorithmic culture in which positive feedback loops are valued for their own sake, regardless of the content. Horror and pain have the same weight as joy and healing. Engagement can always be monetized, no matter what is being engaged. Plenty of liars know how to manipulate these flows. They know how to sell. They know how to meme.

To make the truth gather this same energy, to feed on itself, to spread itself, to push itself to the top of the list—this is one way to make truth into a weapon. It is, however, a dangerous way.

The master’s algorithms will not dismantle the master’s house. Maybe a better way is to break the algorithms—or supersede them with something that aligns with our regard for the truth.

Hari Kunzru

To do this, we have to understand how attention is manipulated to suppress the truth, and how the situation is different from the past. Today, censorship is not just about blocking information, though of course, in countries such as China, this is taking place. Censorship is better understood as the denial of attention. Attention is a finite resource. Censorship can drain it away by distraction, trivialization, or marginalization; by swamping us with things that look like the truth, or that we feel we must address before we turn to the truth. Lying is easy if you are persistent.

Writers who do not know the truth complain in lofty and imprecise terms. They complain about evil in general, and no one who hears them can work out what to do. Such vague descriptions are of little value. They conceal the real forces behind the disaster. If we look, we see that the disaster is caused by certain men.

What we are living through is not a natural catastrophe. Nor can it be understood in terms of “human nature.” If you wish to describe great social and political disasters that are not the product of natural forces or some eternal quality of humankind, you must do so in terms of a practical truth.

You must show that these disasters are launched in order to control those who do not own the means of production. If you wish to write the truth about the disaster, you must write it so that its preventable causes can be identified. If the preventable causes can be identified, the disaster can be fought.

The Judgment to Choose Those in Whose Hands the Truth Will Be Effective

…We think that because what we have written is “on the internet,” everyone will see it. We think that we have spoken and those who wish to hear will hear. But the truth cannot merely be written; the truth must be written for someone, for someone who can do something with it.

The process of recognizing truth is the same for writers and readers, for video bloggers and podcasters and data journalists. Garbage in, garbage out. In order to say good things, your hearing must be good and you must hear good things.

You must strain to hear over the din of cable news. You must speak the truth as deliberately as you listen for it. You must consider to whom you tell the truth and who tells it to you.

You must tell the truth about evil conditions to those for whom the conditions are worst, and you must also learn the truth from them. You must listen to the voices in the icebox at the border.

You must listen to the voices at the Walmart and the warehouse and the care home. You must address not only people who hold certain views but people who, because of their situation, should hold these views.

And you must remember that the audience is continually changing. Even an ICE agent can be addressed when his pay is halted because the government has been shut down, or when his work becomes too hard or dangerous or difficult for him to justify.

The Cunning to Spread the Truth Among the Many

…Writing that stimulates thinking, no matter the field, is useful to the cause of the oppressed. It has the potential to lead to action. What counts is the right kind of thinking—the kind of thinking that investigates the transitory aspect of all things and processes, that stresses change.

Rulers have an intense dislike of change. They would like to see everything remain the same—for a thousand years, if possible. If the sun and moon were to stand still, no one would grow hungry, no one would answer back.

The masseur would always be ready at her table. The towel boy at the side of the pool. The doorman and the driver and the greeter and the caddie and the cleaner and the nurse—all ready. None would refuse to serve. None would ask for a raise.

When the ruler fires a shot, he doesn’t want the enemy to be able to shoot back; his shot, like his word, must always be the last. His image on the poster. His name written first. Always and forever he is the hero of the story.

But the world is not a still image, a movie poster with a single grinning hero. In every condition and every situation, a contradiction appears and grows. All things flow and change, often suddenly and without warning.

To understand and state this is to present a danger to dictators. The center is not holding. Morbid symptoms are appearing. Some of the rulers are morbid symptoms. They tell us that they are causes, but they are merely effects.

Full essay here. See our archives on journalism and truth.