TRU LUV have a mighty ambition - to produce digital rituals that heal us, invoking “tend-and-befriend” over “fight-and-flight”

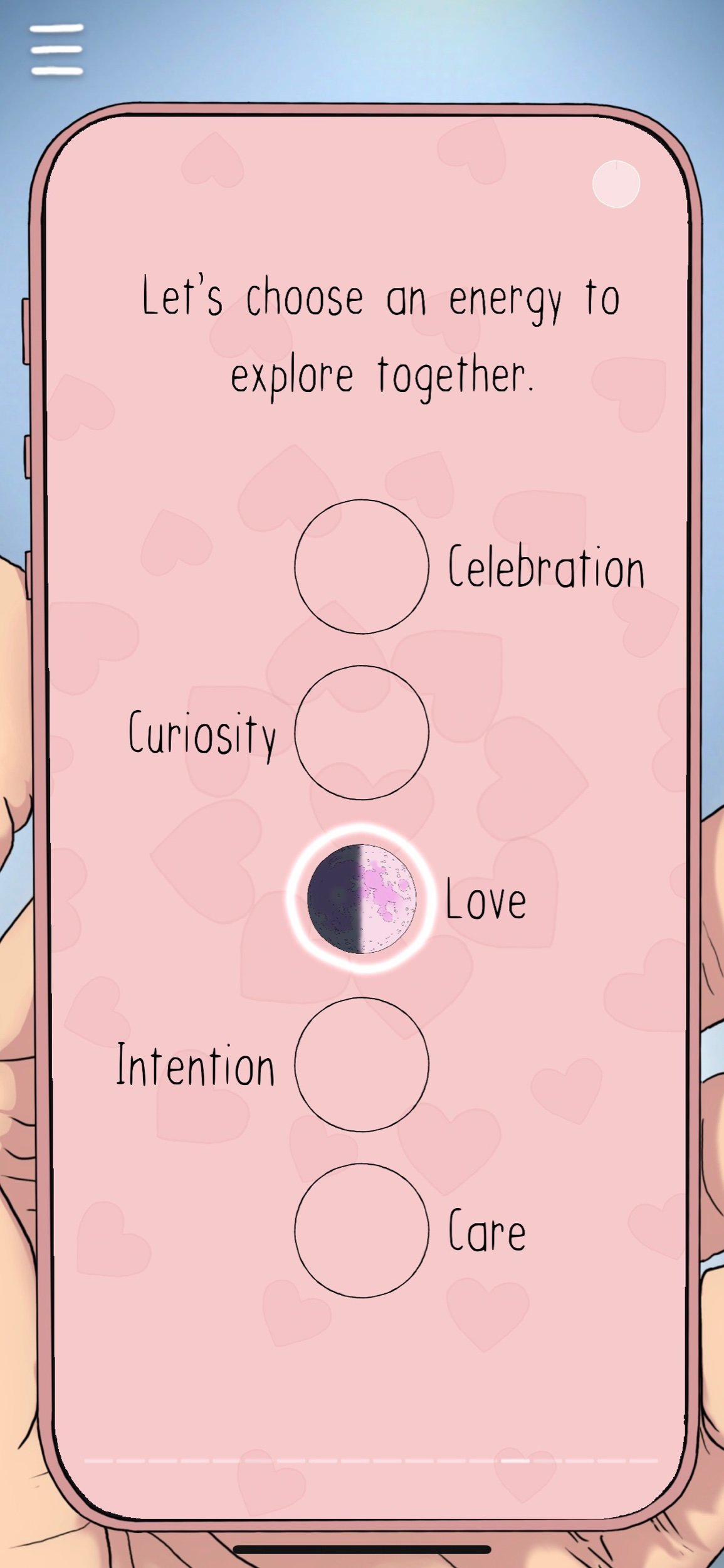

The main interface of TRU LUV’s #SelfCare game

Since the start of A/UK, we’ve been keeping tracks on initiatives and change-makers who want to redesign social media and the digital sphere. This means moving away from the often toxic and destructive tendencies that grip it, and firing up a different spectrum of emotions and mood-states than the usual fear/anger/panic modes.

We’ve just come across a most impressive example of ambitious initiative-taking in this area. TRU LUV (that’s how they spell it) have as their headline ambition, “healing our relationship with technology”.

This isn’t a just wishful thought, distant from execution. Their founder, Brie Code, was a lead AI programmer at the games company Ubisoft, and she leads a team of experts and investors who are multidisciplinary and established.

Above: stills from #SelfCare:

This excerpt from a press release on their 2018 app, #SelfCare, begins to flesh out their vision:

Brie asked her team, “What is AI made by artists and witches?” Their experimental answer: #SelfCare, an app that has no score or winning but instead offers virtual meditative rituals such as laundry, tarot cards and a cat. It was named one of Apple’s Best of 2018 Trend of the Year selections and has surpassed 2 million downloads with no advertising.

“We see futures of caring, pro-social technology,” said Brie. “Within #SelfCare we’ve proven a completely new interaction model of deepening care and compassion as an alternative to the gamification model of rising challenge, fear, shock, or FOMO.”

This is a distinction that TRU LOV’s literature constantly makes. See this from Brie’s own blog:

We make rituals and emotionally conscious AI for personal and community transformation.

Our work is defining a new category of technologically-mediated interfaces that feels like good friendship as an alternative to the existing gamification model built on dominance and reactivity. Our model has the potential to help us all develop greater integrity, compassion and co-creation at all levels of society.

In a 2018 article for the FT, focussing on video games, Brie spells this out even more clearly:

There is a perception problem around games…Media discussion of video games often focuses on violence, gambling or addiction. Many people are put off by these kinds of games. Masculine power fantasies — often a feature of this medium — are not for everyone. For many people, violence and stress are simply uninteresting.

Yet video games can also be spaces for healing, for learning or for connecting with others. I know from my own experiences that interactivity has the power to provide more visceral insight than books or film. Creating games that focus on these aspects could win over new audiences. However, the industry is still largely missing this opportunity.

Lack of diversity in the games industry has led us here. One of my creative directors once told me he wouldn’t put women in our game because it was set in “a time of men”. The games industry is certainly a place of men: only 22 per cent of developers worldwide identify as women. These numbers fall further in creative roles: 10 per cent in game design, 11 per cent in visual arts, 10 per cent in audio and 5 per cent in programming.

Game design theory has been largely written by men and assumes a fight-or-flight response to stress. Most games use frustration to stress the player, then give them chances to win a zero-sum game. However, a study published in 2000 from the University of California, Los Angeles defines a second human stress response, common but little known or studied, called tend-and-befriend. This response may be more prevalent in women.

In 2004, game designer Sheri Graner Ray observed in her book Gender Inclusive Game Design that women tend to like “scenarios that provide mutually beneficial solutions to socially significant situations”. Opportunities for care and connection do exist in video games, but they are often considered the side content.

Tend-and-befriend shows us that mutually beneficial outcomes are as rewarding as winning a fight. This hints at ways to design more interesting video games. Personality psychology and the work done by iThrive, a non-profit body that explores links between positive psychology and games, suggest other possible reward frameworks.

More here. On the current website, TRU LOV defines itself well beyond the games sector, as making:

…caring technology that intrinsically cultivates compassion and creativity in ourselves and each other.

We're creating nourishing experiences for refuge, resilience and transformation by inviting dreamers and leading technologists on a shared journey. Together, we're reimagining technology through our energies of celebration, curiosity, love, intention and care. We're nurturing a new kind of tech company.

We make rituals.

This Globe and Mail article puts TRU LUV’s work in the context of a rising digital wellness industry. But we are excited by their overall ambition, and their underlying theories of how different stretches of the human emotional spectrum can be appealed to, with our digital products.